Anecdotes of the late Samuel Johnson by Hester Lynch Thrale - part 1

Body

Too much intelligence is often as pernicious to biography as too little; the mind remains perplexed by contradiction of probabilities, and finds difficulty in separating report from truth. If Johnson then lamented that so little had ever been said about Butler, I might with more reason be led to complain that so much has been said about himself; for numberless informers but distract or cloud information, as glasses which multiply will for the most part be found also to obscure. Of a life, too, which for the last twenty years was passed in the very front of literature, every leader of a literary company, whether officer or subaltern, naturally becomes either author or critic, so that little less than the recollection that it was once the request of the deceased, and twice the desire of those whose will I ever delighted to comply with, should have engaged me to add my little book to the number of those already written on the subject.

I used to urge another reason for forbearance, and say, that all the readers would, on this singular occasion, be the writers of his life: like the first representation of the

Masque of Comus, which, by changing their characters from spectators to performers, was acted by the lords and ladies it was written to entertain. This objection is, however, now at an end, as I have found friends, far remote indeed from literary questions, who may yet be diverted from melancholy by my description of Johnson's manners, warmed to virtue even by the distant reflection of his glowing excellence, and encouraged by the relation of his animated zeal to persist in the profession as well as practice of Christianity.

Samuel Johnson was the son of Michael Johnson, a bookseller at Lichfield, in Staffordshire; a very pious and worthy man, but wrong-headed, positive, and afflicted with melancholy, as his son, from whom alone I had the information, once told me: his business, however, leading him to be much on horseback, contributed to the preservation of his bodily health and mental sanity, which, when he stayed long at home, would sometimes be about to give way; and Mr. Johnson said, that when his workshop, a detached building, had fallen half down for want of money to repair it, his father was not less diligent to lock the door every night, though he saw that anybody might walk in at the back part, and knew that there was no security obtained by barring the front door. "This," says his son, "was madness, you may see, and would have been discoverable in other instances of the prevalence of imagination, but that poverty prevented it from playing such tricks as riches and leisure encourage".

Michael was a man of still larger size and greater strength than his son, who was reckoned very like him, but did not delight in talking much of his family: "One has," says he, "SO little pleasure in reciting the anecdotes of beggary." One day, however, hearing me praise a favourite friend with partial tenderness as well as true esteem: "Why do you like that man's acquaintance so?" said he. "Because," replied I, "he is open and confiding, and tells me stories of his uncles and cousins; I love the light parts of a solid character." "Nay, if you are for family history," says Mr. Johnson, good-humouredly, "I can fit you: I had an uncle, Cornelius Ford, who, upon a journey, stopped and read an inscription written on a stone he saw standing by the wayside, set up, as it proved, in honour of a man who had leaped a certain leap thereabouts, the extent of which was specified upon the stone: 'Why now,' says my uncle, 'I could leap it in my boots;' and he did leap it in his boots. I had likewise another uncle, Andrew," continued he, "my father's brother, who kept the ring in Smithfield (where they wrestled and boxed) for a whole year, and never was thrown or conquered. Here now are uncles for you, Mistress, if that's the way to your heart."

Mr. Johnson was very conversant in the art of attack and defence by boxing, which science he had learned from this uncle Andrew, I believe; and I have heard him descant upon the age when people were received, and when rejected, in the schools once held for that brutal amusement, much to the admiration of those who had no expectation of his skill in such matters, from the sight of a figure which precluded all possibility of personal prowess; though, because he saw Mr. Thrale one day leap over a cabriolet stool, to show that he was not tired after a chase of fifty miles or more, he suddenly jumped over it too, but in a way so strange and so unwieldy, that our terror lest he should break his bones took from us even the power of laughing.

Michael Johnson was past fifty years old when he married his wife, who was upwards of forty, yet I think her son told me she remained three years childless before he was born into the world, who so greatly contributed to improve it. In three years more she brought another son, Nathaniel, who lived to be twenty-seven or twenty-eight years old, and of whose manly spirit I have heard his brother speak with pride and pleasure, mentioning one circumstance, particular enough, that when the company were one day lamenting the badness of the roads, he inquired where they could be, as he travelled the country more than most people, and had never seen a bad road in his life. The two brothers did not, however, much delight in each other's company, being always rivals for the mother's fondness; and many of the severe reflections on domestic life in Rasselas took their source from its author's keen recollections of the time passed in his early years.

Their father, Michael, died of an inflammatory fever at the age of seventy-six, as Mr. Johnson told me, their mother at eighty-nine, of a gradual decay. She was slight in her person, he said, and rather below than above the common size. So excellent was her character, and so blameless her life, that when an oppressive neighbour once endeavoured to take from her a little field she possessed, he could persuade no attorney to undertake the cause against a woman so beloved in her narrow circle: and it is this incident he alludes to in the line of his "Vanity of Human Wishes," calling her "The general favourite as the general friend." Nor could any one pay more willing homage to such a character, though she had not been related to him, than did Dr. Johnson on every occasion that offered: his disquisition on Pope's epitaph placed over Mrs. Corbet is a proof of that preference always given by him to a noiseless life over a bustling one; but however taste begins, we almost always see that it ends in simplicity; the glutton finishes by losing his relish for anything highly sauced, and calls for his boiled chicken at the close of many years spent in the search of dainties; the connoisseurs are soon weary of Rubens, and the critics of Lucan; and the refinements of every kind heaped upon civil life always sicken their possessors before the close of it.

At the age of two years Mr. Johnson was brought up to London by his mother, to be touched by Queen Anne for the scrofulous evil, which terribly afflicted his childhood, and left such marks as greatly disfigured a countenance naturally harsh and rugged, beside doing irreparable damage to the auricular organs, which never could perform their functions since I knew him; and it was owing to that horrible disorder, too, that one eye was perfectly useless to him; that defect, however, was not observable, the eyes looked both alike. As Mr. Johnson had an astonishing memory, I asked him if he could remember Queen Anne at all? "He had," he said, "a confused, but somehow a sort of solemn, recollection of a lady in diamonds, and a long black hood."

The christening of his brother he remembered with all its circumstances, and said his mother taught him to spell and pronounce the words 'little Natty,' syllable by syllable, making him say it over in the evening to her husband and his guests. The trick which most parents play with their children, that of showing off their newly-acquired accomplishments, disgusted Mr. Johnson beyond expression. He had been treated so himself, he said, till he absolutely loathed his father's caresses, because he knew they were sure to precede some unpleasing display of his early abilities; and he used, when neighbours came o' visiting, to run up a tree that he might not be found and exhibited, such, as no doubt he was, a prodigy of early understanding.

His epitaph upon the duck he killed by treading on it at five years old— "Here lies poor duck That Samuel Johnson trod on; If it had liv'd it had been good luck, For it would have been an odd one"— is a striking example of early expansion of mind and knowledge of language; yet he always seemed more mortified at the recollection of the bustle his parents made with his wit than pleased with the thoughts of possessing it. "That," said he to me one day, "is the great misery of late marriages; the unhappy produce of them becomes the plaything of dotage. An old man's child," continued he, "leads much such a life. I think, as a little boy's dog, teased with awkward fondness, and forced, perhaps, to sit up and beg, as we call it, to divert a company, who at last go away complaining of their disagreeable entertainment."

In consequence of these maxims, and full of indignation against such parents as delight to produce their young ones early into the talking world, I have known Mr. Johnson give a good deal of pain by refusing to hear the verses the children could recite, or the songs they could sing, particularly one friend who told him that his two sons should repeat Gray's "Elegy" to him alternately, that he might judge who had the happiest cadence. "No, pray, sir," said he, "let the dears both speak it at once; more noise will by that means be made, and the noise will be sooner over." He told me the story himself, but I have forgot who the father was.

Mr. Johnson's mother was daughter to a gentleman in the country, such as there were many of in those days, who possessing, perhaps, one or two hundred pounds a year in land, lived on the profits, and sought not to increase their income. She was, therefore, inclined to think higher of herself than of her husband, whose conduct in money matters being but indifferent, she had a trick of teasing him about it, and was, by her son's account, very importunate with regard to her fears of spending more than they could afford, though she never arrived at knowing how much that was, a fault common, as he said, to most women who pride themselves on their economy. They did not, however, as I could understand, live ill together on the whole. "My father," says he, "could always take his horse and ride away for orders when things went badly." The lady's maiden name was Ford; and the parson who sits next to the punch-bowl in Hogarth's "Modern Midnight Conversation" was her brother's son.

This Ford was a man who chose to be eminent only for vice, with talents that might have made him conspicuous in literature, and respectable in any profession he could have chosen. His cousin has mentioned him in the lives of Fenton and of Broome; and when he spoke of him to me it was always with tenderness, praising his acquaintance with life and manners, and recollecting one piece of advice that no man surely ever followed more exactly: "Obtain," says Ford, "some general principles of every science; he who can talk only on one subject, or act only in one department, is seldom wanted, and perhaps never wished for, while the man of general knowledge can often benefit, and always please." He used to relate, however, another story less to the credit of his cousin's penetration, how Ford on some occasion said to him, "You will make your way the more easily in the world, I see, as you are contented to dispute no man's claim to conversation excellence; they will, therefore, more willingly allow your pretensions as a writer." Can one, on such an occasion, forbear recollecting the predictions of Boileau's father, when stroking the head of the young satirist?—"Ce petit bon homme," says he, "n'a point trop d'esprit, mais il ne dira jamais mal de personne." Such are the prognostics formed by men of wit and sense, as these two certainly were, concerning the future character and conduct of those for whose welfare they were honestly and deeply concerned; and so late do those features of peculiarity come to their growth, which mark a character to all succeeding generations.

Dr. Johnson first learned to read of his mother and her old maid Catharine, in whose lap he well remembered sitting while she explained to him the story of St. George and the Dragon. I know not whether this is the proper place to add that such was his tenderness, and such his gratitude, that he took a journey to Lichfield fifty-seven years afterwards to support and comfort her in her last illness; he had inquired for his nurse, and she was dead. The recollection of such reading as had delighted him in his infancy made him always persist in fancying that it was the only reading which could please an infant; and he used to condemn me for putting Newbery's books into their hands as too trifling to engage their attention. "Babies do not want," said he, "to hear about babies; they like to be told of giants and castles, and of somewhat which can stretch and stimulate their little minds."

When in answer I would urge the numerous editions and quick sale of "Tommy Prudent" or "Goody Two-Shoes." "Remember always," said he, "that the parents buy the books, and that the children never read them." Mrs. Barbauld, however, had his best praise, and deserved it; no man was more struck than Mr. Johnson with voluntary descent from possible splendour to painful duty. At eight years old he went to school, for his health would not permit him to be sent sooner; and at the age of ten years his mind was disturbed by scruples of infidelity, which preyed upon his spirits and made him very uneasy, the more so as he revealed his uneasiness to no one, being naturally, as he said, "of a sullen temper and reserved disposition."

He searched, however, diligently but fruitlessly, for evidences of the truth of revelation; and at length, recollecting a book he had once seen in his father's shop, entitled "De Veritate Religionis," etc., he began to think himself highly culpable for neglecting such a means of information, and took himself severely to task for this sin, adding many acts of voluntary, and to others unknown, penance. The first opportunity which offered, of course, he seized the book with avidity, but on examination, not finding himself scholar enough to peruse its contents, set his heart at rest; and, not thinking to inquire whether there were any English books written on the subject, followed his usual amusements, and considered his conscience as lightened of a crime.

He redoubled his diligence to learn the language that contained the information he most wished for, but from the pain which guilt had given him he now began to deduce the soul's immortality, which was the point that belief first stopped at; and from that moment, resolving to be a Christian, became one of the most zealous and pious ones our nation ever produced. When he had told me this odd anecdote of his childhood, "I cannot imagine," said he, "what makes me talk of myself to you so, for I really never mentioned this foolish story to anybody except Dr. Taylor, not even to my dear, dear Bathurst, whom I loved better than ever I loved any human creature; but poor Bathurst is dead!" Here a long pause and a few tears ensued. "Why, sir," said I, "how like is all this to Jean Jacques Rousseau—as like, I mean, as the sensations of frost and fire, when my child complained yesterday that the ice she was eating burned her mouth." Mr. Johnson laughed at the incongruous ideas, but the first thing which presented itself to the mind of an ingenious and learned friend whom I had the pleasure to pass some time with here at Florence was the same resemblance, though I think the two characters had little in common, further than an early attention to things beyond the capacity of other babies, a keen sensibility of right and wrong, and a warmth of imagination little consistent with sound and perfect health.

I have heard him relate another odd thing of himself too, but it is one which everybody has heard as well as me: how, when he was about nine years old, having got the play of Hamlet in his hand, and reading it quietly in his father's kitchen, he kept on steadily enough till, coming to the Ghost scene, he suddenly hurried upstairs to the street door that he might see people about him. Such an incident, as he was not unwilling to relate it, is probably in every one's possession now; he told it as a testimony to the merits of Shakespeare. But one day, when my son was going to school, and dear Dr. Johnson followed as far as the garden gate, praying for his salvation in a voice which those who listened attentively could hear plain enough, he said to me suddenly, "Make your boy tell you his dreams: the first corruption that entered into my heart was communicated in a dream." "What was it, sir?" said I. "Do not ask me," replied he, with much violence, and walked away in apparent agitation. I never durst make any further inquiries.

He retained a strong aversion for the memory of Hunter, one of his schoolmasters, who, he said, once was a brutal fellow, "so brutal," added he, "that no man who had been educated by him ever sent his son to the same school." I have, however, heard him acknowledge his scholarship to be very great. His next master he despised, as knowing less than himself, I found, but the name of that gentleman has slipped my memory.

Mr. Johnson was himself exceedingly disposed to the general indulgence of children, and was even scrupulously and ceremoniously attentive not to offend them.

Mr. Johnson was himself exceedingly disposed to the general indulgence of children, and was even scrupulously and ceremoniously attentive not to offend them; he had strongly persuaded himself of the difficulty people always find to erase early impressions either of kindness or resentment, and said "he should never have so loved his mother when a man had she not given him coffee she could ill afford, to gratify his appetite when a boy." "If you had had children, sir," said I, "would you have taught them anything?" "I hope," replied he, "that I should have willingly lived on bread and water to obtain instruction for them; but I would not have set their future friendship to hazard for the sake of thrusting into their heads knowledge of things for which they might not perhaps have either taste or necessity. You teach your daughters the diameters of the planets, and wonder when you have done that they do not delight in your company. No science can be communicated by mortal creatures without attention from the scholar; no attention can be obtained from children without the infliction of pain, and pain is never remembered without resentment."

That something should be learned was, however, so certainly his opinion that I have heard him say how education had been often compared to agriculture, yet that it resembled it chiefly in this: "That if nothing is sown, no crop," says he, "can be obtained." His contempt of the lady who fancied her son could be eminent without study, because Shakespeare was found wanting in scholastic learning, was expressed in terms so gross and so well known, I will not repeat them here. To recollect, however, and to repeat the sayings of Dr. Johnson, is almost all that can be done by the writers of his life, as his life, at least since my acquaintance with him, consisted in little else than talking, when he was not absolutely employed in some serious piece of work; and whatever work he did seemed so much below his powers of performance that he appeared the idlest of all human beings, ever musing till he was called out to converse, and conversing till the fatigue of his friends, or the promptitude of his own temper to take offence, consigned him back again to silent meditation.

The remembrance of what had passed in his own childhood made Mr. Johnson very solicitous to preserve the felicity of children: and when he had persuaded Dr. Sumner to remit the tasks usually given to fill up boys' time during the holidays, he rejoiced exceedingly in the success of his negotiation, and told me that he had never ceased representing to all the eminent schoolmasters in England the absurd tyranny of poisoning the hour of permitted pleasure by keeping future misery before the children's eyes, and tempting them by bribery or falsehood to evade it. "Bob Sumner," said he, "however, I have at length prevailed upon. I know not, indeed, whether his tenderness was persuaded, or his reason convinced, but the effect will always be the same. Poor Dr. Sumner died, however, before the next vacation."

Mr. Johnson was of opinion, too, that young people should have positive, not general, rules given for their direction. "My mother," said he, "was always telling me that I did not behave myself properly, that I should endeavour to learn behaviour, and such cant; but when I replied that she ought to tell me what to do, and what to avoid, her admonitions were commonly, for that time at least, at an end." This I fear was, however, at best a momentary refuge found out by perverseness. No man knew better than Johnson in how many nameless and numberless actions behaviour consists—actions which can scarcely be reduced to rule, and which come under no description. Of these he retained so many very strange ones, that I suppose no one who saw his odd manner of gesticulating much blamed or wondered at the good lady's solicitude concerning her son's behaviour.

Though he was attentive to the peace of children in general, no man had a stronger contempt than he for such parents as openly profess that they cannot govern their children. "How," says he, "is an army governed? Such people, for the most part, multiply prohibitions till obedience becomes impossible, and authority appears absurd, and never suspect that they tease their family, their friends, and themselves, only because conversation runs low, and something must be said." Of parental authority, indeed, few people thought with a lower degree of estimation. I one day mentioned the resignation of Cyrus to his father's will, as related by Xenophon, when, after all his conquests, he requested the consent of Cambyses to his marriage with a neighbouring princess, and I added Rollin's applause and recommendation of the example. "Do you not perceive, then," says Johnson, "that Xenophon on this occasion commends like a pedant, and Pere Rollin applauds like a slave? If Cyrus by his conquests had not purchased emancipation, he had conquered to little purpose indeed. Can you forbear to see the folly of a fellow who has in his care the lives of thousands, when he begs his papa permission to be married, and confesses his inability to decide in a matter which concerns no man's happiness but his own?"

Mr. Johnson caught me another time reprimanding the daughter of my housekeeper for having sat down unpermitted in her mother's presence. "Why, she gets her living, does she not," said he, "without her mother's help? Let the wench alone," continued he. And when we were again out of the women's sight who were concerned in the dispute: "Poor people's children, dear lady," said he, "never respect them. I did not respect my own mother, though I loved her. And one day, when in anger she called me a puppy, I asked her if she knew what they called a puppy's mother."

We were talking of a young fellow who used to come often to the house; he was about fifteen years old, or less, if I remember right, and had a manner at once sullen and sheepish. "That lad," says Mr. Johnson, "looks like the son of a schoolmaster, which," added he, "is one of the very worst conditions of childhood. Such a boy has no father, or worse than none; he never can reflect on his parent but the reflection brings to his mind some idea of pain inflicted, or of sorrow suffered." I will relate one thing more that Dr. Johnson said about babyhood before I quit the subject; it was this: "That little people should be encouraged always to tell whatever they hear particularly striking to some brother, sister, or servant immediately, before the impression is erased by the intervention of newer occurrences. He perfectly remembered the first time he ever heard of Heaven and Hell," he said, "because when his mother had made out such a description of both places as she thought likely to seize the attention of her infant auditor, who was then in bed with her, she got up, and dressing him before the usual time, sent him directly to call a favourite workman in the house, to whom he knew he would communicate the conversation while it was yet impressed upon his mind. The event was what she wished, and it was to that method chiefly that he owed his uncommon felicity of remembering distant occurrences and long past conversations."

At the age of eighteen Dr. Johnson quitted school, and escaped from the tuition of those he hated or those he despised. I have heard him relate very few college adventures. He used to say that our best accounts of his behaviour there would be gathered from Dr. Adams and Dr. Taylor, and that he was sure they would always tell the truth. He told me, however, one day how, when he was first entered at the University, he passed a morning, in compliance with the customs of the place, at his tutor's chambers; but, finding him no scholar, went no more. In about ten days after, meeting the same gentleman, Mr. Jordan, in the street, he offered to pass by without saluting him; but the tutor stopped, and inquired, not roughly neither, what he had been doing? "Sliding on the ice," was the reply, and so turned away with disdain. He laughed very heartily at the recollection of his own insolence, and said they endured it from him with wonderful acquiescence, and a gentleness that, whenever he thought of it, astonished himself.

He told me, too, that when he made his first declamation, he wrote over but one copy, and that coarsely; and having given it into the hand of the tutor, who stood to receive it as he passed, was obliged to begin by chance and continue on how he could, for he had got but little of it by heart; so fairly trusting to his present powers for immediate supply, he finished by adding astonishment to the applause of all who knew how little was owing to study. A prodigious risk, however, said some one. "Not at all!" exclaims Johnson. "No man, I suppose, leaps at once into deep water who does not know how to swim." I doubt not but this story will be told by many of his biographers, and said so to him when he told it me on the 18th of July, 1773. "And who will be my biographer," said he, "do you think?" "Goldsmith, no doubt," replied I, "and he will do it the best among us." "The dog would write it best, to be sure," replied he; "but his particular malice towards me, and general disregard for truth, would make the book useless to all, and injurious to my character." "Oh! as to that," said I, "we should all fasten upon him, and force him to do you justice; but the worst is, the Doctor does not know your life; nor can I tell indeed who does, except Dr. Taylor of Ashbourne." "Why, Taylor," said he, "is better acquainted with my heart than any man or woman now alive; and the history of my Oxford exploits lies all between him and Adams; but Dr. James knows my very early days better than he. After my coming to London to drive the world about a little, you must all go to Jack Hawkesworth for anecdotes. I lived in great familiarity with him (though I think there was not much affection) from the year 1753 till the time Mr. Thrale and you took me up. I intend, however, to disappoint the rogues, and either make you write the life, with Taylor's intelligence, or, which is better, do it myself, after outliving you all. I am now," added he, "keeping a diary, in hopes of using it for that purpose some time."

Here the conversation stopped, from my accidentally looking in an old magazine of the year 1768, where I saw the following lines with his name to them, and asked if they were his:— Verses said to be written by Dr. Samuel Johnson, at the request of a gentleman to whom a lady had given a sprig of myrtle.

What hopes, what terrors, does thy gift create,

Ambiguous emblem of uncertain fate;

The myrtle, ensign of supreme command,

Consigned by Venus to Melissa's hand:

Not less capricious than a reigning fair,

Now grants, and now rejects a lover's prayer.

In myrtle shades oft sings the happy swain,

In myrtle shades despairing ghosts complain:

The myrtle crowns the happy lovers' heads,

The unhappy lover's grave the myrtle spreads:

Oh, then, the meaning of thy gift impart,

And ease the throbbings of an anxious heart!

Soon must this bough, as you shall fix his doom,

Adorn Philander's head, or grace his tomb.

"Why, now, do but see how the world is gaping for a wonder!" cries Mr. Johnson. "_I think it is now just forty years ago that a young fellow had a sprig of myrtle given him by a girl he courted, and asked me to write him some verses that he might present her in return. I promised, but forgot; and when he called for his lines at the time agreed on—'Sit still a moment,' says I, 'dear Mund, and I'll fetch them thee,' so stepped aside for five minutes, and wrote the nonsense you now keep such a stir about."

Upon revising these anecdotes, it is impossible not to be struck with shame and regret that one treasured no more of them up; but no experience is sufficient to cure the vice of negligence. Whatever one sees constantly, or might see constantly, becomes uninteresting; and we suffer every trivial occupation, every slight amusement, to hinder us from writing down what, indeed, we cannot choose but remember, but what we should wish to recollect with pleasure, unpoisoned by remorse for not remembering more. While I write this, I neglect impressing my mind with the wonders of art and beauties of nature that now surround me; and shall one day, perhaps, think on the hours I might have profitably passed in the Florentine Gallery, and reflecting on Raphael's St. John at that time, as upon Johnson's conversation in this moment, may justly exclaim of the months spent by me most delightfully in Italy— "That I prized every hour that passed by, Beyond all that had pleased me before; But now they are past, and I sigh And I grieve that I prized them no more." Shenstone.

Dr. Johnson delighted in his own partiality for Oxford; and one day, at my house, entertained five members of the other University with various instances of the superiority of Oxford, enumerating the gigantic names of many men whom it had produced, with apparent triumph. At last I said to him, "Why, there happens to be no less than five Cambridge men in the room now." "I did not," said he, "think of that till you told me; but the wolf don't count the sheep." When the company were retired, we happened to be talking of Dr. Barnard, the Provost of Eton, who died about that time; and after a long and just eulogium on his wit, his learning, and his goodness of heart, "He was the only man, too," says Mr. Johnson, quite seriously, "that did justice to my good breeding; and you may observe that I am well-bred to a degree of needless scrupulosity. No man," continued he, not observing the amazement of his hearers, "no man is so cautious not to interrupt another; no man thinks it so necessary to appear attentive when others are speaking; no man so steadily refuses preference to himself, or so willingly bestows it on another, as I do; nobody holds so strongly as I do the necessity of ceremony, and the ill effects which follow the breach of it, yet people think me rude; but Barnard did me justice." "'Tis pity," said I, laughing, "that he had not heard you compliment the Cambridge men after dinner to-day." "Why," replied he, "I was inclined to down them sure enough; but then a fellow deserves to be of Oxford that talks so."

I have heard him at other times relate how he used so sit in some coffee-house there, and turn M----'s "C-r-ct-c-s" into ridicule for the diversion of himself and of chance comers-in. "The 'Elf-da,'" says he, "was too exquisitely pretty; I could make no fun out of that." When upon some occasions he would express his astonishment that he should have an enemy in the world, while he had been doing nothing but good to his neighbours, I used to make him recollect these circumstances. "Why, child," said he, "what harm could that do the fellow? I always thought very well of M----n for a Cambridge man; he is, I believe, a mighty blameless character."

Such tricks were, however, the more unpardonable in Mr. Johnson, because no one could harangue like him about the difficulty always found in forgiving petty injuries, or in provoking by needless offence. Mr. Jordan, his tutor, had much of his affection, though he despised his want of scholastic learning. "That creature would," said he, "defend his pupils to the last: no young lad under his care should suffer for committing slight improprieties, while he had breath to defend, or power to protect them. If I had had sons to send to College," added he, "Jordan should have been their tutor."

Sir William Browne, the physician, who lived to a very extraordinary age, and was in other respects an odd mortal, with more genius than understanding, and more self sufficiency than wit, was the only person who ventured to oppose Mr. Johnson when he had a mind to shine by exalting his favourite university, and to express his contempt of the Whiggish notions which prevail at Cambridge. He did it once, however, with surprising felicity. His antagonist having repeated with an air of triumph the famous epigram written by Dr. Trapp— "Our royal master saw, with heedful eyes, The wants of his two universities: Troops he to Oxford sent, as knowing why That learned body wanted loyalty: But books to Cambridge gave, as well discerning That that right loyal body wanted learning." Which, says Sir William, might well be answered thus:—

"The King to Oxford sent his troop of horse, For Tories own no argument but force; With equal care to Cambridge books he sent, For Whigs allow no force but argument." Mr. Johnson did him the justice to say it was one of the happiest extemporaneous productions he ever met with, though he once comically confessed that he hated to repeat the wit of a Whig urged in support of Whiggism. Says Garrick to him one day, "Why did not you make me a Tory, when we lived so much together? You love to make people Tories." "Why," says Johnson, pulling a heap of halfpence from his pocket, "did not the king make these guineas?"

Of Mr. Johnson's Toryism the world has long been witness, and the political pamphlets written by him in defence of his party are vigorous and elegant. He often delighted his imagination with the thoughts of having destroyed Junius, an anonymous writer who flourished in the years 1769 and 1770, and who kept himself so ingeniously concealed from every endeavour to detect him that no probable guess was, I believe, ever formed concerning the author's name, though at that time the subject of general conversation. Mr. Johnson made us all laugh one day, because I had received a remarkably fine Stilton cheese as a present from some person who had packed and directed it carefully, but without mentioning whence it came. Mr. Thrale, desirous to know who we were obliged to, asked every friend as they came in, but nobody owned it. "Depend upon it, sir," says Johnson, "it was sent by Junius."

The "False Alarm," his first and favourite pamphlet, was written at our house between eight o'clock on Wednesday night and twelve o'clock on Thursday night. We read it to Mr. Thrale when he came very late home from the House of Commons; the other political tracts followed in their order. I have forgotten which contains the stroke at Junius, but shall for ever remember the pleasure it gave him to have written it. It was, however, in the year 1775 that Mr. Edmund Burke made the famous speech in Parliament that struck even foes with admiration, and friends with delight. Among the nameless thousands who are contented to echo those praises they have not skill to invent, I ventured, before Dr. Johnson himself, to applaud with rapture the beautiful passage in it concerning Lord Bathurst and the Angel, which, said our Doctor, had I been in the house, I would have answered thus:—

Suppose, Mr. Speaker, that to Wharton or to Marlborough, or to any of the eminent Whigs of the last age, the devil had, not with any great impropriety, consented to appear, he would, perhaps, in somewhat like these words, have commenced the conversation: 'You seem, my lord, to be concerned at the judicious apprehension that while you are sapping the foundations of royalty at home, and propagating here the dangerous doctrine of resistance, the distance of America may secure its inhabitants from your arts, though active. But I will unfold to you the gay prospects of futurity. This people, now so innocent and harmless, shall draw the sword against their mother country, and bathe its point in the blood of their benefactors; this people, now contented with a little, shall then refuse to spare what they themselves confess they could not miss; and these men, now so honest and so grateful, shall, in return for peace and for protection, see their vile agents in the House of Parliament, there to sow the seeds of sedition, and propagate confusion, perplexity, and pain. Be not dispirited, then, at the contemplation of their present happy state: I promise you that anarchy, poverty, and death shall, by my care, be carried even across the spacious Atlantic, and settle in America itself, the sure consequences of our beloved Whiggism.'

This I thought a thing so very particular that I begged his leave to write it down directly, before anything could intervene that might make me forget the force of the expressions. A trick which I have, however, seen played on common occasions, of sitting steadily down at the other end of the room to write at the moment what should be said in company, either by Dr. Johnson or to him, I never practised myself, nor approved of in another. There is something so ill-bred, and so inclining to treachery in this conduct, that were it commonly adopted all confidence would soon be exiled from society, and a conversation assembly-room would become tremendous as a court of justice. A set of acquaintance joined in familiar chat may say a thousand things which, as the phrase is, pass well enough at the time, though they cannot stand the test of critical examination; and as all talk beyond that which is necessary to the purposes of actual business is a kind of game, there will be ever found ways of playing fairly or unfairly at it, which distinguish the gentleman from the juggler.

Dr. Johnson, as well as many of my acquaintance, knew that I kept a common-place book, and he one day said to me good-humouredly that he would give me something to write in my repository. "I warrant," said he, "_there is a great deal about me in it. You shall have at least one thing worth your pains, so if you will get the pen and ink I will repeat to you

Anacreon's 'Dove' directly; but tell at the same time that as I never was struck with anything in the Greek language till I read that, so I never read anything in the same language since that pleased me as much. I hope my translation," continued he, "_is not worse than that of Frank Fawkes." Seeing me disposed to laugh, "Nay, nay," said he, "Frank Fawkes has done them very finely."

Lovely courier of the sky,

Whence and whither dost thou fly?

Scatt'ring, as thy pinions play,

Liquid fragrance all the way.

Is it business? is it love?

Tell me, tell me, gentle Dove.

'Soft Anacreon's vows I bear,

Vows to Myrtale the fair;

Graced with all that charms the heart,

Blushing nature, smiling art.

Venus, courted by an ode,

On the bard her Dove bestowed.

Vested with a master's right

Now Anacreon rules my flight;

His the letters that you see,

Weighty charge consigned to me;

Think not yet my service hard,

Joyless task without reward;

Smiling at my master's gates,

Freedom my return awaits.

But the liberal grant in vain

Tempts me to be wild again.

Can a prudent Dove decline

Blissful bondage such as mine?

Over hills and fields to roam,

Fortune's guest without a home;

Under leaves to hide one's head,

Slightly sheltered, coarsely fed;

Now my better lot bestows

Sweet repast, and soft repose;

Now the generous bowl I sip

As it leaves Anacreon's lip;

Void of care, and free from dread,

From his fingers snatch his bread,

Then with luscious plenty gay,

Round his chamber dance and play;

Or from wine, as courage springs,

O'er his face extend my wings;

And when feast and frolic tire,

Drop asleep upon his lyre.

This is all, be quick and go,

More than all thou canst not know;

Let me now my pinions ply,

I have chattered like a pie.

When I had finished, "But you must remember to add," says Mr. Johnson, "that though these verses were planned, and even begun, when I was sixteen years old, I never could find time to make an end of them before I was sixty-eight." This facility of writing, and this dilatoriness ever to write, Mr. Johnson always retained, from the days that he lay abed and dictated his first publication to Mr. Hector, who acted as his amanuensis, to the moment he made me copy out those variations in Pope's "Homer" which are printed in the "Poets' Lives." "And now," said he, when I had finished it for him, "I fear not Mr. Nicholson of a pin."

The fine 'Rambler,' on the subject of Procrastination, was hastily composed, as I have heard, in Sir Joshua Reynolds's parlour, while the boy waited to carry it to press; and numberless are the instances of his writing under immediate pressure of importunity or distress. He told me that the character of Sober in the 'Idler' was by himself intended as his own portrait, and that he had his own outset into life in his eye when he wrote the Eastern story of "Gelaleddin."

Of the allegorical papers in the 'Rambler,' Labour and Rest was his favourite; but Scrotinus, the man who returns late in life to receive honours in his native country, and meets with mortification instead of respect, was by him considered as a masterpiece in the science of life and manners. The character of Prospero in the fourth volume Garrick took to be his; and I have heard the author say that he never forgave the offence. Sophron was likewise a picture drawn from reality, and by Gelidus, the philosopher, he meant to represent Mr. Coulson, a mathematician, who formerly lived at Rochester.

The man immortalised for purring like a cat was, as he told me, one Busby, a proctor in the Commons. He who barked so ingeniously, and then called the drawer to drive away the dog, was father to Dr. Salter, of the Charterhouse. He who sang a song, and by correspondent motions of his arm chalked out a giant on the wall, was one Richardson, an attorney. The letter signed "Sunday" was written by Miss Talbot; and he fancied the billets in the first volume of the 'Rambler' were sent him by Miss Mulso, now Mrs. Chapone. The papers contributed by Mrs. Carter had much of his esteem, though he always blamed me for preferring the letter signed "Chariessa" to the allegory, where religion and superstition are indeed most masterly delineated.

When Dr. Johnson read his own satire, in which the life of a scholar is painted, with the various obstructions thrown in his way to fortune and to fame, he burst into a passion of tears one day. The family and Mr. Scott only were present, who, in a jocose way, clapped him on the back, and said, "What's all this, my dear sir? Why, you and I and hercules, you know, were all troubled with melancholy."

As there are many gentlemen of the same name, I should say, perhaps, that it was a Mr. Scott who married Miss Robinson, and that I think I have heard Mr. Thrale call him George Lowis, or George Augustus, I have forgot which. He was a very large man, however, and made out the triumvirate with Johnson and Hercules comically enough. The Doctor was so delighted at his odd sally that he suddenly embraced him, and the subject was immediately changed. I never saw Mr. Scott but that once in my life. Dr. Johnson was liberal enough in granting literary assistance to others, I think; and innumerable are the prefaces, sermons, lectures, and dedications which he used to make for people who begged of him.

Mr. Murphy related in his and my hearing one day, and he did not deny it, that when Murphy joked him the week before for having been so diligent of late between Dodd's sermon and Kelly's prologue, Dr. Johnson replied, "Why, sir, when they come to me with a dead staymaker and a dying parson, what can a man do?" He said, however, that "he hated to give away literary performances, or even to sell them too cheaply. The next generation shall not accuse me," added he, "of beating down the price of literature. One hates, besides, ever to give that which one has been accustomed to sell. Would not you, sir," turning to Mr. Thrale, "rather give away money than porter?"

Mr. Johnson had never, by his own account, been a close student, and used to advise young people never to be without a book in their pocket, to be read at bye-times when they had nothing else to do. "It has been by that means," said he to a boy at our house one day, "that all my knowledge has been gained, except what I have picked up by running about the world with my wits ready to observe, and my tongue ready to talk. A man is seldom in a humour to unlock his bookcase, set his desk in order, and betake himself to serious study; but a retentive memory will do something, and a fellow shall have strange credit given him, if he can but recollect striking passages from different books, keep the authors separate in his head, and bring his stock of knowledge artfully into play. How else," added he, "do the gamesters manage when they play for more money than they are worth?"

His Dictionary, however, could not, one would think, have been written by running up and down; but he really did not consider it as a great performance; and used to say "that he might have done it easily in two years had not his health received several shocks during the time." When Mr. Thrale, in consequence of this declaration, teased him in the year 1768 to give a new edition of it, because, said he, there are four or five gross faults: "Alas! sir," replied Johnson, "there are four or five hundred faults instead of four or five; but you do not consider that it would take me up three whole months' labour, and when the time was expired the work would not be done." When the booksellers set him about it, however, some years after, he went cheerfully to the business, said he was well paid, and that they deserved to have it done carefully. His reply to the person who complimented him on its coming out first, mentioning the ill success of the French in a similar attempt, is well known, and, I trust, has been often recorded. "Why, what would you expect, dear sir," said he, "from fellows that eat frogs?"

I have, however, often thought Dr. Johnson more free than prudent in professing so loudly his little skill in the Greek language; for though he considered it as a proof of a narrow mind to be too careful of literary reputation, yet no man could be more enraged than he if an enemy, taking advantage of this confession, twitted him with his ignorance; and I remember when the King of Denmark was in England one of his noblemen was brought by Mr. Colman to see Dr. Johnson at our country house, and having heard, he said, that he was not famous for Greek literature, attacked him on the weak side, politely adding that he chose that conversation on purpose to favour himself.

Our Doctor, however, displayed so copious, so compendious a knowledge of authors, books, and every branch of learning in that language, that the gentleman appeared astonished. When he was gone home, says Johnson, "Now, for all this triumph I may thank Thrale's Xenophon here, as I think, excepting that one, I have not looked in a Greek book these ten years; but see what haste my dear friends were all in," continued he, "to tell this poor innocent foreigner that I know nothing of Greek! Oh, no, he knows nothing of Greek!" with a loud burst of laughing.

When Davies printed the "Fugitive Pieces" without his knowledge or consent, "How," said I, "would Pope have raved, had he been served so!" "We should never," replied he, "have heard the last on't, to be sure; but then Pope was a narrow man. I will, however," added he, "storm and bluster myself a little this time," so went to London in all the wrath he could muster up. At his return I asked how the affair ended. "Why," said he, "I was a fierce fellow, and pretended to be very angry; and Thomas was a good-natured fellow, and pretended to be very sorry; so there the matter ended. I believe the dog loves me dearly. Mr. Thrale," turning to my husband, "what shall you and I do that is good for Tom Davies? We will do something for him, to be sure."

Of Pope as a writer he had the highest opinion, and once when a lady at our house talked of his preface to Shakespeare as superior to Pope's, "I fear not, madam," said he, "the little fellow has done wonders." His superior reverence of Dryden, notwithstanding, still appeared in his talk as in his writings; and when some one mentioned the ridicule thrown on him in the 'Rehearsal,' as having hurt his general character as an author, "On the contrary," says Mr. Johnson, "the greatness of Dryden's reputation is now the only principle of vitality which keeps the Duke of Buckingham's play from putrefaction."

It was not very easy, however, for people not quite intimate with Dr. Johnson to get exactly his opinion of a writer's merit, as he would now and then divert himself by confounding those who thought themselves obliged to say to-morrow what he had said yesterday; and even Garrick, who ought to have been better acquainted with his tricks, professed himself mortified that one time when he was extolling Dryden in a rapture that I suppose disgusted his friend, Mr. Johnson suddenly challenged him to produce twenty lines in a series that would not disgrace the poet and his admirer.

Garrick produced a passage that he had once heard the Doctor commend, in which he now found, if I remember rightly, sixteen faults, and made Garrick look silly at his own table.

When I told Mr. Johnson the story, "Why, what a monkey was David now," says he, "to tell of his own disgrace!" And in the course of that hour's chat he told me how he used to tease Garrick by commendations of the tomb-scene in Congreve's 'Mourning Bride,' protesting, that Shakespeare had in the same line of excellence nothing as good. "All which is strictly true," said he; "but that is no reason for supposing Congreve is to stand in competition with Shakespeare: these fellows know not how to blame, nor how to commend."

I forced him one day, in a similar humour, to prefer Young's description of "Night" to the so much admired ones of Dryden and Shakespeare, as more forcible and more general. Every reader is not either a lover or a tyrant, but every reader is interested when he hears that "Creation sleeps; 'tis as the general pulse Of life stood still, and nature made a pause; An awful pause—prophetic of its end." "This," said he, "is true; but remember that, taking the compositions of Young in general, they are but like bright stepping-stones over a miry road. Young froths and foams, and bubbles sometimes very vigorously; but we must not compare the noise made by your tea-kettle here with the roaring of the ocean."

Somebody was praising Corneille one day in opposition to Shakespeare. "Corneille is to Shakespeare," replied Mr. Johnson, "as a clipped hedge is to a forest." When we talked of Steele's Essays, "They are too thin," says our critic, "for an Englishman's taste: mere superficial observations on life and manners, without erudition enough to make them keep, like the light French wines, which turn sour with standing awhile for want of body, as we call it." Of a much-admired poem, when extolled as beautiful, he replied, "That it had indeed the beauty of a bubble. The colours are gay," said he, "but the substance slight."

Of James Harris's Dedication to his "Hermes," I have heard him observe that, though but fourteen lines long, there were six grammatical faults in it. A friend was praising the style of Dr. Swift; Mr. Johnson did not find himself in the humour to agree with him: the critic was driven from one of his performances to the other. At length, "You must allow me," said the gentleman, "that there are strong facts in the account of 'The Four Last Years of Queen Anne.'" "Yes, surely, sir," replies Johnson, "and so there are in the Ordinary of Newgate's account."

This was like the story which Mr. Murphy tells, and Johnson always acknowledged: how Mr. Rose of Hammersmith, contending for the preference of Scotch writers over the English, after having set up his authors like ninepins, while the Doctor kept bowling them down again; at last, to make sure of victory, he named Ferguson upon "Civil Society," and praised the book for being written in a new manner. "I do not," says Johnson, "perceive the value of this new manner; it is only like Buckinger, who had no hands, and so wrote with his feet." Of a modern Martial, when it came out: "There are in these verses," says Dr. Johnson, "too much folly for madness, I think, and too much madness for folly."

|

Hester Lynch Thrale née Salusbury 1741 - 2 May 1821 |

|---|---|

| Hester Thrale | Family tree and portraits · Homes · Works · Writings . Thraliana · Pets · Travels · 80th party · Criticism · Death · Obituaries |

| Henry Thrale | Courtship · Marriage dowry · Marriage · Children · 13th anniversary |

| Gabriel Piozzi | Marriage · 7th anniversary · Adopted son · Miscarried daughter |

| People | Samuel Johnson · Streatham Worthies · Proposal from Mr. Swale · King Louis XVI & Queen Marie Antoinette |

| Writings about | The Thrales of Streatham Park · Dr Johnsons Women · Intimate letters · Hester Lynch Piozzi · Dr Johnsons Women · Doctor Johnson's Mrs Thrale · By Samuel Johnson: Ode to · 35th verses · By Herbert Lawrence: Song to Hester |

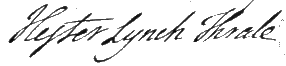

| Signature |  |