Anecdotes of the late Samuel Johnson by Hester Lynch Thrale - part 4

The truth is, nobody suffered more from pungent sorrow at a friend's death than Johnson, though he would suffer no one else to complain of their losses in the same way; "for," says he, "we must either outlive our friends, you know, or our friends must outlive us; and I see no man that would hesitate about the choice." Mr. Johnson loved late hours extremely, or more properly hated early ones. Nothing was more terrifying to him than the idea of retiring to bed, which he never would call going to rest, or suffer another to call so. "I lie down," said he, "that my acquaintance may sleep; but I lie down to endure oppressive misery, and soon rise again to pass the night in anxiety and pain." By this pathetic manner, which no one ever possessed in so eminent a degree, he used to shock me from quitting his company, till I hurt my own health not a little by sitting up with him when I was myself far from well; nor was it an easy matter to oblige him even by compliance, for he always maintained that no one forbore their own gratifications for the sake of pleasing another, and if one did sit up it was probably to amuse oneself.

Some right, however, he certainly had to say so, as he made his company exceedingly entertaining when he had once forced one, by his vehement lamentations and piercing reproofs, not to quit the room, but to sit quietly and make tea for him, as I often did in London till four o'clock in the morning. At Streatham, indeed, I managed better, having always some friend who was kind enough to engage him in talk, and favour my retreat. The first time I ever saw this extraordinary man was in the year 1764, when Mr. Murphy, who had been long the friend and confidential intimate of Mr. Thrale, persuaded him to wish for Johnson's conversation, extolling it in terms which that of no other person could have deserved, till we were only in doubt how to obtain his company, and find an excuse for the invitation.

The celebrity of Mr. Woodhouse, a shoemaker, whose verses were at that time the subject of common discourse, soon afforded a pretence, and Mr. Murphy brought Johnson to meet him, giving me general cautions not to be surprised at his figure, dress, or behaviour. What I recollect best of the day's talk was his earnestly recommending Addison's works to Mr. Woodhouse as a model for imitation. "Give nights and days, sir," said he, "to the study of Addison, if you mean either to be a good writer, or what is more worth, an honest man." When I saw something like the same expression in his criticism on that author, lately published, I put him in mind of his past injunctions to the young poet, to which he replied, "that he wished the shoemaker might have remembered them as well."

Mr. Johnson liked his new acquaintance so much, however, that, from that time he dined with us every Thursday through the winter, and in the autumn of the next year he followed us to Brighthelmstone, whence we were gone before his arrival; so he was disappointed and enraged, and wrote us a letter expressive of anger, which we were very desirous to pacify, and to obtain his company again, if possible. Mr. Murphy brought him back to us again very kindly, and from that time his visits grew more frequent, till in the year 1766 his health, which he had always complained of, grew so exceedingly bad, that he could not stir out of his room in the court he inhabited for many weeks together- -I think months.

Mr. Thrale's attentions and my own now became so acceptable to him, that he often lamented to us the horrible condition of his mind, which he said was nearly distracted; and though he charged us to make him odd solemn promises of secrecy on so strange a subject, yet when we waited on him one morning, and heard him, in the most pathetic terms, beg the prayers of Dr. Delap, who had left him as we came in, I felt excessively affected with grief, and well remember my husband involuntarily lifted up one hand to shut his mouth, from provocation at hearing a man so wildly proclaim what he could at last persuade no one to believe, and what, if true, would have been so very unfit to reveal.

Mr. Thrale went away soon after, leaving me with him, and bidding me prevail on him to quit his close habitation in the court and come with us to Streatham, where I undertook the care of his health, and had the honour and happiness of contributing to its restoration. This task, though distressing enough sometimes, would have been less so had not my mother and he disliked one another extremely, and teased me often with perverse opposition, petty contentions, and mutual complaints. Her superfluous attention to such accounts of the foreign politics as are transmitted to us by the daily prints, and her willingness to talk on subjects he could not endure, began the aversion; and when, by the peculiarity of his style, she found out that he teased her by writing in the newspapers concerning battles and plots which had no existence, only to feed her with new accounts of the division of Poland, perhaps, or the disputes between the States of Russia and Turkey, she was exceedingly angry, to be sure, and scarcely, I think, forgave the offence till the domestic distresses of the year 1772 reconciled them to and taught them the true value of each other, excellent as they both were, far beyond the excellence of any other man and woman I ever yet saw. As her conduct, too, extorted his truest esteem, her cruel illness excited all his tenderness, nor was the sight of beauty, scarce to be subdued by disease, and wit, flashing through the apprehension of evil, a scene which Dr. Johnson could see without sensibility. He acknowledged himself improved by her piety, and astonished at her fortitude, and hung over her bed with the affection of a parent, and the reverence of a son. Nor did it give me less pleasure to see her sweet mind cleared of all its latent prejudices, and left at liberty to admire and applaud that force of thought and versatility of genius, that comprehensive soul and benevolent heart, which attracted and commanded veneration from all, but inspired peculiar sensations of delight mixed with reverence in those who, like her, had the opportunity to observe these qualities stimulated by gratitude, and actuated by friendship.

When Mr. Thrale's perplexities disturbed his peace, dear Dr. Johnson left him scarce a moment, and tried every artifice to amuse as well as every argument to console him: nor is it more possible to describe than to forget his prudent, his pious attentions towards the man who had some years before certainly saved his valuable life, perhaps his reason, by half obliging him to change the foul air of Fleet Street for the wholesome breezes of the Sussex Downs.

The epitaph engraved on my mother's monument shows how deserving she was of general applause. I asked Johnson why he named her person before her mind. He said it was "because everybody could judge of the one, and but few of the other."

Juxta sepulta est HESTERA MARIA Thomae Cotton de Combermere baronetti Cestriensis filia, Johannis Salusbury armigeri Flintiensis uxor. Forma felix, felix ingenio: Omnibus jucunda, suorum amantissima. Linguis artibusque ita exculta Ut loquenti nunquam deessent Sermonis nitor, sententiarum flosculi, Sapientiae gravitas, leporum gratia: Modum servandi adeo perita, Ut domestica inter negotia literis oblectaretur. Literarum inter delicias, rem familiarem sedulo curaret, Multis illi multos annos precantibus diri carcinomatis veneno contabuit, nexibusque vitae paulatim resolutis, e terris--meliora sperans--emigravit. Nata 1707. Nupta 1739. Obiit 1773.

Mr. Murphy, who admired her talents and delighted in her company, did me the favour to paraphrase this elegant inscription in verses which I fancy have never yet been published. His fame has long been out of my power to increase as a poet: as a man of sensibility perhaps these lines may set him higher than he now stands. I remember with gratitude the friendly tears which prevented him from speaking as he put them into my hand. Near this place Are deposited the remains of HESTER MARIA, The daughter of Sir Thomas Cotton of Combermere, in the county of Cheshire, Bart., the wife of John Salusbury, of the county of Flint, Esquire. She was born in the year 1707, married in 1739, and died in 1773.

A pleasing form, where every grace combined,

With genius blest, a pure enlightened mind;

Benevolence on all that smiles bestowed,

A heart that for her friends with love o'erflowed:

In language skilled, by science formed to please,

Her mirth was wit, her gravity was ease.

Graceful in all, the happy mien she knew,

Which even to virtue gives the limits due;

Whate'er employed her, that she seemed to choose,

Her house, her friends, her business, or the muse.

Admired and loved, the theme of general praise,

All to such virtue wished a length of days.

But sad reverse! with slow-consuming pains,

Th' envenomed cancer revelled in her veins;

Preyed on her spirits--stole each power away;

Gradual she sank, yet smiling in decay;

She smiled in hope, by sore affliction tried,

And in that hope the pious Christian died.

The following epitaph on Mr. Thrale, who has now a monument close by hers in Streatham Church, I have seen printed and commended in Maty's Review for April, 1784; and a friend has favoured me with the translation:--

Hic conditur quod reliquum est HENRICI THRALE, Qui res seu civiles, seu domesticas, ita egit, Ut vitam illi longiorem multi optarent; Ita sacras, Ut quam brevem esset habiturus praescire videretur. Simplex, apertus, sibique semper similis, Nihil ostentavit aut arte fictum aut cura Elaboratum. In senatu, regi patriaeque Fideliter studuit; Vulgi obstrepentis contemptor animosus, Domi inter mille mercaturae negotia Literarum elegantiam minime neglexit. Amicis quocunque modo laborantibus, Conciliis, auctoritate, muneribus adfuit. Inter familiares, comites, convivas, hospites, Tam facili fuit morum suavitate Ut omnium animos ad se alliceret; Tam felici sermonis libertate Ut nulli adulatus, omnibus placeret. Natus 1724. Ob. 1781. Consortes tumuli habet Rodolphum patrem, strenuum fortemque virum, et Henricum filium unicum, quem spei parentum mors inopina decennem praeripuit. Ita Domus felix et opulenta, quam erexit Avus, auxitque pater, cum nepote decidit. Abi viator! Et vicibus rerum humanarum perspectis, AEternitatem cogita!

Here are deposited the remains of HENRY THRALE, Who managed all his concerns in the present world, public and private, in such a manner as to leave many wishing he had continued longer in it; And all that related to a future world, as if he had been sensible how short a time he was to continue in this. Simple, open, and uniform in his manners, his conduct was without either art or affectation. In the senate steadily attentive to the true interests of his king and country, He looked down with contempt on the clamours of the multitude: Though engaged in a very extensive business, He found some time to apply to polite literature And was ever ready to assist his friends labouring under any difficulties, with his advice, his influence, and his purse. To his friends, acquaintance, and guests, he behaved with such sweetness of manners as to attach them all to his person: So happy in his conversation with them, as to please all, though he flattered none. He was born in the year 1724, and died in 1781. In the same tomb lie interred his father, Ralph Thrale, a man of vigour and activity, And his only son Henry, who died before his father, Aged ten years. Thus a happy and opulent family, Raised by the grandfather, and augmented by the father, became extinguished with the grandson. Go, Reader! And reflecting on the vicissitudes of all human affairs, Meditate on eternity.

I never recollect to have heard that Dr. Johnson wrote inscriptions for any sepulchral stones except Dr. Goldsmith's, in Westminster Abbey, and these two in Streatham Church. He made four lines once on the death of poor Hogarth, which were equally true and pleasing. I know not why Garrick's were preferred to them. "The hand of him here torpid lies, That drew th' essential form of grace; Here clos'd in death th' attentive eyes, That saw the manners in the face."

Mr. Hogarth, among the variety of kindnesses shown to me when I was too young to have a proper sense of them, was used to be very earnest that I should obtain the acquaintance, and if possible the friendship, of Dr. Johnson, whose conversation was, to the talk of other men, "like Titian's painting compared to Hudson's," he said: "but don't you tell people, now, that I say so," continued he, "for the connoisseurs and I are at war, you know; and because I hate them, they think I hate Titian--and let them!"

Many were indeed the lectures I used to have in my very early days from dear Mr. Hogarth, whose regard for my father induced him, perhaps, to take notice of his little girl, and give her some odd particular directions about dress, dancing, and many other matters, interesting now only because they were his. As he made all his talents, however, subservient to the great purposes of morality, and the earnest desire he had to mend mankind, his discourse commonly ended in an ethical dissertation, and a serious charge to me, never to forget his picture of the "Lady's Last Stake."

Of Dr. Johnson, when my father and he were talking together about him one day, "That man," says Hogarth, "is not contented with believing the Bible, but he fairly resolves, I think, to believe nothing but the Bible. Johnson," added he, "though so wise a fellow, is more like King David than King Solomon; for he says in his haste that 'all men are liars.'" This charge, as I afterwards came to know, was but too well founded.

Mr. Johnson's incredulity amounted almost to disease, and I have seen it mortify his companions exceedingly. But the truth is, Mr. Thrale had a very powerful influence over the Doctor, and could make him suppress many rough answers. He could likewise prevail on him to change his shirt, his coat, or his plate, almost before it came indispensably necessary to the comfort of his friends. But as I never had any ascendency at all over Mr. Johnson, except just in the things that concerned his health, it grew extremely perplexing and difficult to live in the house with him when the master of it was no more; the worse, indeed, because his dislikes grew capricious; and he could scarce bear to have anybody come to the house whom it was absolutely necessary for me to see.

Two gentlemen, I perfectly well remember, dining with us at Streatham in the summer, 1782, when Elliot's brave defence of Gibraltar was a subject of common discourse, one of these men naturally enough began some talk about red-hot balls thrown with surprising dexterity and effect, which Dr. Johnson having listened some time to, "I would advise you, sir," said he, with a cold sneer, "never to relate this story again; you really can scarce imagine how very poor a figure you make in the telling of it." Our guest being bred a Quaker, and, I believe, a man of an extremely gentle disposition, needed no more reproofs for the same folly; so if he ever did speak again, it was in a low voice to the friend who came with him. The check was given before dinner, and after coffee I left the room. When in the evening, however, our companions were returned to London, and Mr. Johnson and myself were left alone, with only our usual family about us, "I did not quarrel with those Quaker fellows," said he, very seriously. "You did perfectly right," replied I, "for they gave you no cause of offence." "No offence!" returned he, with an altered voice; "and is it nothing, then, to sit whispering together when _I am present, without ever directing their discourse towards me, or offering me a share in the conversation?" "_That was because you frighted him who spoke first about those hot balls." "Why, madam, if a creature is neither capable of giving dignity to falsehood, nor willing to remain contented with the truth, he deserves no better treatment."

Mr. Johnson's fixed incredulity of everything he heard, and his little care to conceal that incredulity, was teasing enough, to be sure; and I saw Mr. Sharp was pained exceedingly when relating the history of a hurricane that happened about that time in the West Indies, where, for aught I know, he had himself lost some friends too, he observed Dr. Johnson believed not a syllable of the account. "For 'tis so easy," says he, "for a man to fill his mouth with a wonder, and run about telling the lie before it can be detected, that I have no heart to believe hurricanes easily raised by the first inventor, and blown forwards by thousands more." I asked him once if he believed the story of the destruction of Lisbon by an earthquake when it first happened. "Oh! not for six months," said he, "at least. I did think that story too dreadful to be credited, and can hardly yet persuade myself that it was true to the full extent we all of us have heard."

Among the numberless people, however, whom I heard him grossly and flatly contradict, I never yet saw any one who did not take it patiently excepting Dr. Burney, from whose habitual softness of manners I little expected such an exertion of spirit; the event was as little to be expected. Mr. Johnson asked his pardon generously and genteelly, and when he left the room, rose up to shake hands with him, that they might part in peace. On another occasion, when he had violently provoked Mr. Pepys, in a different but perhaps not a less offensive manner, till something much too like a quarrel was grown up between them, the moment he was gone, "Now," says Dr. Johnson, "is Pepys gone home hating me, who love him better than I did before. He spoke in defence of his dead friend; but though I hope _I spoke better who spoke against him, yet all my eloquence will gain me nothing but an honest man for my enemy!" He did not, however, cordially love Mr. Pepys, though he respected his abilities. "_I know the dog was a scholar," said he when they had been disputing about the classics for three hours together one morning at Streatham, "but that he had so much taste and so much knowledge I did not believe. I might have taken Barnard's word though, for Barnard would not lie."

We had got a little French print among us at Brighthelmstone, in November, 1782, of some people skating, with these lines written under:--

Sur un mince chrystal l'hyver conduit leurs pas,

Le precipice est sous la glace;

Telle est de nos plaisirs la legere surface,

Glissez mortels; n'appayez pas.

And I begged translation from everybody. Dr. Johnson gave me this:--

O'er ice the rapid skater flies,

With sport above and death below;

Where mischief lurks in gay disguise,

Thus lightly touch and quickly go.

He was, however, most exceedingly enraged when he knew that in the course of the season I had asked half-a-dozen acquaintance to do the same thing; and said,

it was a piece of treachery, and done to make everybody else look little when compared to my favourite friends the Pepyses, whose translations were unquestionably the best.

I will insert them, because he did say so. This is the distich given me by Sir Lucas, to whom I owe more solid obligations, no less than the power of thanking him for the life he saved, and whose least valuable praise is the correctness of his taste:--

O'er the ice as o'er pleasure you lightly should glide,

Both have gulfs which their flattering surfaces hide.

This other more serious one was written by his brother:--

Swift o'er the level how the skaters slide,

And skim the glitt'ring surface as they go:

Thus o'er life's specious pleasures lightly glide,

But pause not, press not on the gulf below.

Dr. Johnson seeing this last, and thinking a moment, repeated:--

O'er crackling ice, o'er gulfs profound,

With nimble glide the skaters play;

O'er treacherous pleasure's flow'ry ground

Thus lightly skim, and haste away.

Though thus uncommonly ready both to give and take offence, Mr. Johnson had many rigid maxims concerning the necessity of continued softness and compliance of disposition: and when I once mentioned Shenstone's idea that some little quarrel among lovers, relations, and friends was useful, and contributed to their general happiness upon the whole, by making the soul feel her elastic force, and return to the beloved object with renewed delight: "Why, what a pernicious maxim is this now," cries Johnson, "All quarrels ought to be avoided studiously, particularly conjugal ones, as no one can possibly tell where they may end; besides that lasting dislike is often the consequence of occasional disgust, and that the cup of life is surely bitter enough without squeezing in the hateful rind of resentment."

It was upon something like the same principle, and from his general hatred of refinement, that when I told him how Dr. Collier, in order to keep the servants in humour with his favourite dog, by seeming rough with the animal himself on many occasions, and crying out, "Why will nobody knock this cur's brains out?" meant to conciliate their tenderness towards Pompey; he returned me for answer, "that the maxim was evidently false, and founded on ignorance of human life: that the servants would kick the dog sooner for having obtained such a sanction to their severity. And I once," added he, "chid my wife for beating the cat before the maid, who will now," said I, "treat puss with cruelty, perhaps, and plead her mistress's example."

I asked him upon this if he ever disputed with his wife? (I had heard that he loved her passionately.) "Perpetually," said he: "my wife had a particular reverence for cleanliness, and desired the praise of neatness in her dress and furniture, as many ladies do, till they become troublesome to their best friends, slaves to their own besoms, and only sigh for the hour of sweeping their husbands out of the house as dirt and useless lumber. 'A clean floor is so comfortable,' she would say sometimes, by way of twitting; till at last I told her that I thought we had had talk enough about the floor, we would now have a touch at the ceiling."

On another occasion I have heard him blame her for a fault many people have, of setting the miseries of their neighbours half unintentionally, half wantonly before their eyes, showing them the bad side of their profession, situation, etc. He said, "She would lament the dependence of pupilage to a young heir, etc., and once told a waterman who rowed her along the Thames in a wherry, that he was no happier than a galley-slave, one being chained to the oar by authority, the other by want. I had, however," said he, laughing, "the wit to get her daughter on my side always before we began the dispute. She read comedy better than anybody he ever heard," he said; "in tragedy she mouthed too much."

Garrick told Mr. Thrale, however, that she was a little painted puppet, of no value at all, and quite disguised with affectation, full of odd airs of rural elegance; and he made out some comical scenes, by mimicking her in a dialogue he pretended to have overheard. I do not know whether he meant such stuff to be believed or no, it was so comical; nor did I indeed ever see him represent her ridiculously, though my husband did.

The intelligence I gained of her from old Levett was only perpetual illness and perpetual opium. The picture I found of her at Lichfield was very pretty, and her daughter, Mrs. Lucy Porter, said it was like. Mr. Johnson has told me that her hair was eminently beautiful, quite blonde, like that of a baby; but that she fretted about the colour, and was always desirous to dye it black, which he very judiciously hindered her from doing. His account of their wedding we used to think ludicrous enough. "I was riding to church," says Johnson, "and she following on another single horse. She hung back, however, and I turned about to see whether she could get her steed along, or what was the matter. I had, however, soon occasion to see it was only coquetry, and that I despised, so quickening my pace a little, she mended hers; but I believe there was a tear or two--pretty dear creature!"

Johnson loved his dinner exceedingly, and has often said in my hearing, perhaps for my edification, "that wherever the dinner is ill got there is poverty or there is avarice, or there is stupidity; in short, the family is somehow grossly wrong: for," continued he, "a man seldom thinks with more earnestness of anything than he does of his dinner, and if he cannot get that well dressed, he should be suspected of inaccuracy in other things." One day, when he was speaking upon the subject, I asked him if he ever huffed his wife about his dinner? "So often," replied he, "that at last she called to me, and said, 'Nay, hold, Mr. Johnson, and do not make a farce of thanking God for a dinner which in a few minutes you will protest not eatable.'"

When any disputes arose between our married acquaintance, however, Mr. Johnson always sided with the husband, "whom," he said, "the woman had probably provoked so often, she scarce knew when or how she had disobliged him first. Women," says Dr. Johnson, "give great offence by a contemptuous spirit of non-compliance on petty occasions. The man calls his wife to walk with him in the shade, and she feels a strange desire just at that moment to sit in the sun: he offers to read her a play, or sing her a song, and she calls the children in to disturb them, or advises him to seize that opportunity of settling the family accounts. Twenty such tricks will the faithfullest wife in the world not refuse to play, and then look astonished when the fellow fetches in a mistress.

Boarding-schools were established," continued he, "for the conjugal quiet of the parents. The two partners cannot agree which child to fondle, nor how to fondle them, so they put the young ones to school, and remove the cause of contention. The little girl pokes her head, the mother reproves her sharply. 'Do not mind your mamma,' says the father, 'my dear, but do your own way.' The mother complains to me of this. 'Madam,' said I, 'your husband is right all the while; he is with you but two hours of the day, perhaps, and then you tease him by making the child cry. Are not ten hours enough for tuition? and are the hours of pleasure so frequent in life, that when a man gets a couple of quiet ones to spend in familiar chat with his wife, they must be poisoned by petty mortifications? Put missy to school; she will learn to hold her head like her neighbours, and you will no longer torment your family for want of other talk.'".

The vacuity of life had at some early period of his life struck so forcibly on the mind of Mr. Johnson, that it became by repeated impression his favourite hypothesis, and the general tenor of his reasonings commonly ended there, wherever they might begin. Such things, therefore, as other philosophers often attribute to various and contradictory causes, appeared to him uniform enough; all was done to fill up the time, upon his principle. I used to tell him that it was like the clown's answer in As You Like It, of "Oh, lord, sir!" for that it suited every occasion. One man, for example, was profligate and wild, as we call it, followed the girls, or sat still at the gaming-table. "Why, life must be filled up," says Johnson, "and the man who is not capable of intellectual pleasures must content himself with such as his senses can afford." Another was a hoarder. "Why, a fellow must do something; and what, so easy to a narrow mind as hoarding halfpence till they turn into sixpences."

Avarice was a vice against which, however, I never much heard Mr. Johnson declaim, till one represented it to him connected with cruelty, or some such disgraceful companion. "Do not," said he, "discourage your children from hoarding if they have a taste to it: whoever lays up his penny rather than part with it for a cake, at least is not the slave of gross appetite, and shows besides a preference always to be esteemed, of the future to the present moment. Such a mind may be made a good one; but the natural spendthrift, who grasps his pleasures greedily and coarsely, and cares for nothing but immediate indulgence, is very little to be valued above a negro."

We talked of Lady Tavistock, who grieved herself to death for the loss of her husband--"She was rich, and wanted employment," says Johnson, "so she cried till she lost all power of restraining her tears: other women are forced to outlive their husbands, who were just as much beloved, depend on it; but they have no time for grief: and I doubt not, if we had put my Lady Tavistock into a small chandler's shop, and given her a nurse-child to tend, her life would have been saved. The poor and the busy have no leisure for sentimental sorrow."

We were speaking of a gentleman who loved his friend--"Make him Prime Minister," says Johnson, "and see how long his friend will be remembered." But he had a rougher answer for me, when I commended a sermon preached by an intimate acquaintance of our own at the trading end of the town. "What was the subject, madam?" says Dr. Johnson. "Friendship, sir," replied I. "Why, now, is it not strange that a wise man, like our dear little Evans, should take it in his head to preach on such a subject, in a place where no one can be thinking of it?" "Why, what are they thinking upon, sir?" said I. "Why, the men are thinking on their money, I suppose, and the women are thinking of their mops."

Dr. Johnson's knowledge and esteem of what we call low or coarse life was indeed prodigious; and he did not like that the upper ranks should be dignified with the name of the world. Sir Joshua Reynolds said one day that nobody wore laced coats now; and that once everybody wore them. "See, now," says Johnson, "how absurd that is; as if the bulk of mankind consisted of fine gentlemen that came to him to sit for their pictures. If every man who wears a laced coat (that he can pay for) was extirpated, who would miss them?"

With all this haughty contempt of gentility, no praise was more welcome to Dr. Johnson than that which said he had the notions or manners of a gentleman: which character I have heard him define with accuracy, and describe with elegance. "Officers," he said, "were falsely supposed to have the carriage of gentlemen; whereas no profession left a stronger brand behind it than that of a soldier; and it was the essence of a gentleman's character to bear the visible mark of no profession whatever." He once named Mr. Berenger as the standard of true elegance; but some one objecting that he too much resembled the gentleman in

Congreve's comedies, Mr. Johnson said, "We must fix them upon the famous Thomas Hervey, whose manners were polished even to acuteness and brilliancy, though he lost but little in solid power of reasoning, and in genuine force of mind."

Mr. Johnson had, however, an avowed and scarcely limited partiality for all who bore the name or boasted the alliance of an Aston or a Hervey; and when Mr. Thrale once asked him which had been the happiest period of his past life? he replied, "It was that year in which he spent one whole evening with Molly Aston. That, indeed," said he, "was not happiness, it was rapture; but the thoughts of it sweetened the whole year." I must add that the evening alluded to was not passed tete-a-tete, but in a select company, of which the present Lord Killmorey was one. "Molly," says Dr. Johnson, "was a beauty and a scholar, and a wit and a Whig; and she talked all in praise of liberty: and so I made this epigram upon her. She was the loveliest creature I ever saw!!!

Liber ut esse velim, suasisti pulchra Maria,

Ut maneam liber-- pulchra Maria, vale!

"Will it do this way in English, sir?" said I.

Persuasions to freedom fall oddly from you;

If freedom we seek--fair Maria, adieu!

"It will do well enough," replied he, "but it is translated by a lady, and the ladies never loved Molly Aston." I asked him what his wife thought of this attachment? "She was jealous, to be sure," said he, "and teased me sometimes when I would let her; and one day, as a fortune-telling gipsy passed us when we were walking out in company with two or three friends in the country, she made the wench look at my hand, but soon repented her curiosity; 'for,' says the gipsy, 'your heart is divided, sir, between a Betty and a Molly: Betty loves you best, but you take most delight in Molly's company.' When I turned about to laugh, I saw my wife was crying. Pretty charmer! she had no reason!"

It was, I believe, long after the currents of life had driven him to a great distance from this lady, that he spent much of his time with Mrs. F-tzh--b--t, of whom he always spoke with esteem and tenderness, and with a veneration very difficult to deserve. "That woman," said he, "_loved her husband as we hope and desire to be loved by our guardian angel. F-tzh--b- -t was a gay, good-humoured fellow, generous of his money and of his meat, and desirous of nothing but cheerful society among people distinguished in some way, in any way, I think; for

Rousseau and St. Austin would have been equally welcome to his table and to his kindness. The lady, however, was of another way of thinking: her first care was to preserve her husband's soul from corruption; her second, to keep his estate entire for their children: and I owed my good reception in the family to the idea she had entertained, that I was fit company for F-tzh--b--t, whom I loved extremely. 'They dare not,' said she, 'swear, and take other conversation-liberties before you.'" I asked if her husband returned her regard? "_He felt her influence too powerfully," replied Mr. Johnson; "no man will be fond of what forces him daily to feel himself inferior. She stood at the door of her paradise in Derbyshire, like the angel with a flaming sword, to keep the devil at a distance. But she was not immortal, poor dear! she died, and her husband felt at once afflicted and released." I inquired if she was handsome? "She would have been handsome for a queen," replied the panegyrist; "her beauty had more in it of majesty than of attraction, more of the dignity of virtue than the vivacity of wit."

The friend of this lady, Miss B--thby, succeeded her in the management of Mr. F-tzh--b--t's family, and in the esteem of Dr. Johnson, though he told me she pushed her piety to bigotry, her devotion to enthusiasm, that she somewhat disqualified herself for the duties of this life, by her perpetual aspirations after the next. Such was, however, the purity of her mind, he said, and such the graces of her manner, that Lord Lyttelton and he used to strive for her preference with an emulation that occasioned hourly disgust, and ended in lasting animosity. "You may see," said he to me, when the "Poets' Lives" were printed, "that dear B--thby is at my heart still. She would delight in that fellow Lyttelton's company though, all that I could do; and I cannot forgive even his memory the preference given by a mind like hers." I have heard Baretti say that when this lady died, Dr. Johnson was almost distracted with his grief, and that the friends about him had much ado to calm the violence of his emotion.

Dr. Taylor, too, related once to Mr. Thrale and me, that when he lost his wife, the negro Francis ran away, though in the middle of the night, to Westminster, to fetch Dr. Taylor to his master, who was all but wild with excess of sorrow, and scarce knew him when he arrived. After some minutes, however, the Doctor proposed their going to prayers, as the only rational method of calming the disorder this misfortune had occasioned in both their spirits. Time, and resignation to the will of God, cured every breach in his heart before I made acquaintance with him, though he always persisted in saying he never rightly recovered the loss of his wife. It is in allusion to her that he records the observation of a female critic, as he calls her, in Gray's "Life;" and the lady of great beauty and elegance, mentioned in the criticisms upon Pope's epitaphs, was Miss Molly Aston. The person spoken of in his strictures upon Young's poetry is the writer of these anecdotes, to whom he likewise addressed the following verses when he was in the Isle of Skye with Mr. Boswell.

The letters written in his journey, I used to tell him, were better than the printed book; and he was not displeased at my having taken the pains to copy them all over. Here is the Latin ode:--

Permeo terras, ubi nuda rupes

Saxeas miscet nebulis ruinas,

Torva ubi rident steriles coloni Rura labores.

Pervagor gentes, hominum ferorum

Vita ubi nullo decorata cultu,

Squallet informis, tigurique fumis Faeda latescit.

Inter erroris salebrosa longi,

Inter ignotae strepitus loquelae,

Quot modis mecum, quid agat requiro Thralia dulcis?

Seu viri curas pia nupta mulcet,

Seu fovet mater sobolem benigna,

Sive cum libris novitate pascit Sedula mentem:

Sit memor nostri, fideique merces,

Stet fides constans, meritoque blandum

Thraliae discant resonare nomen Littora Skiae.

On another occasion I can boast verses from Dr. Johnson. As I went into his room the morning of my birthday once, and said to him, "Nobody sends me any verses now, because I am five-and-thirty years old, and Stella was fed with them till forty-six, I remember." My being just recovered from illness and confinement will account for the manner in which he burst out, suddenly, for so he did without the least previous hesitation whatsoever, and without having entertained the smallest intention towards it half a minute before:

Oft in danger, yet alive, We are come to thirty-five;

Long may better years arrive, Better years than thirty-five.

Could philosophers contrive Life to stop at thirty-five,

Time his hours should never drive O'er the bounds of thirty-five.

High to soar, and deep to dive, Nature gives at thirty-five.

Ladies, stock and tend your hive, Trifle not at thirty-five:

For howe'er we boast and strive, Life declines from thirty-five.

He that ever hopes to thrive Must begin by thirty-five;

And all who wisely wish to wive Must look on Thrale at thirty-five.

"And now," said he, as I was writing them down, "you may see what it is to come for poetry to a dictionary-maker; you may observe that the rhymes run in alphabetical order exactly." And so they do. Mr. Johnson did indeed possess an almost Tuscan power of improvisation. When he called to my daughter, who was consulting with a friend about a new gown and dressed hat she thought of wearing to an assembly, thus suddenly, while she hoped he was not listening to their conversation--

Wear the gown and wear the hat,

Snatch thy pleasures while they last;

Hadst thou nine lives like a cat,

Soon those nine lives would be past.

It is impossible to deny to such little sallies the power of the Florentines, who do not permit their verses to be ever written down, though they often deserve it, because, as they express it, Cosi se perde-rebbe la poca gloria.

As for translations, we used to make him sometimes run off with one or two in a good humour. He was praising this song of Metastasio:--

Deh, se piacermi vuoi,

Lascia i sospetti tuoi,

Non mi turbar conquesto

Molesto dubitar:

Chi ciecamente crede,

Impegna a serbar fede:

Chi sempre inganno aspetta,

Alletta ad ingannar.

"Should you like it in English," said he, "thus?"

Would you hope to gain my heart,

Bid your teasing doubts depart;

He who blindly trusts,

will find Faith from every generous mind:

He who still expects deceit,

Only teaches how to cheat.

|

Hester Lynch Thrale née Salusbury 1741 - 2 May 1821 |

|---|---|

| Hester Thrale | Family tree and portraits · Homes · Works · Writings . Thraliana · Pets · Travels · 80th party · Criticism · Death · Obituaries |

| Henry Thrale | Courtship · Marriage dowry · Marriage · Children · 13th anniversary |

| Gabriel Piozzi | Marriage · 7th anniversary · Adopted son · Miscarried daughter |

| People | Samuel Johnson · Streatham Worthies · Proposal from Mr. Swale · King Louis XVI & Queen Marie Antoinette |

| Writings about | The Thrales of Streatham Park · Dr Johnsons Women · Intimate letters · Hester Lynch Piozzi · Dr Johnsons Women · Doctor Johnson's Mrs Thrale · By Samuel Johnson: Ode to · 35th verses · By Herbert Lawrence: Song to Hester |

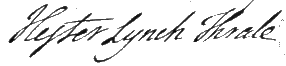

| Signature |  |